1939 BSA WM20 Motorcycle

The BSA M20 and M21 side valves were introduced in 1937 and owe their existence to the drafting pen of Valentine (Val) Page—the same highly-talented ex-JAP and ex-Ariel designer responsible for machines such as the technically creditable (if stylistically wanting) Triumph 6/1, the redoubtable BSA Gold Star and, not least, a wide range of highly underrated Ariel singles.

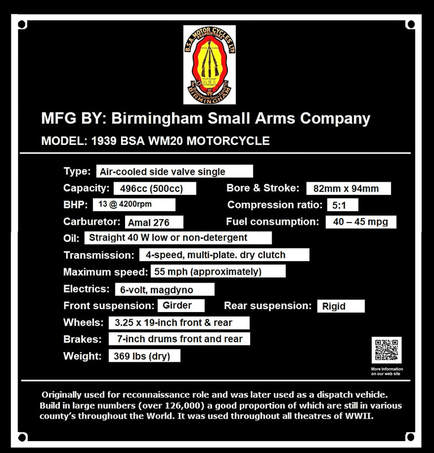

Discontinued in 1963 (1955 for the M20), two engine sizes were listed by the Birmingham Small Arms Company; the 496cc M20 (82mm x 94mm), and the 591cc M21 (85mm x 105mm up to 1938, and 82mm x 112mm thereafter). Both bikes started out with hand change, rigid frames and girder forks. That was pretty much the pre-war state-of-the-side valve-art.

In general, the engines are strong and stress free. They should all start on the first or second kick and settle into a low, steady (and soft) beat. The procedure is straightforward; tickle the carb, set a little retard on the ignition, bring the piston over TDC (with or without the valve lifter) and swing through gently and firmly. And keep in mind that it's really the last few kick start degrees that does the job, so don't ease off halfway down.

Different examples, naturally enough, will have slightly different starting routine. Some want choke. Some don't. Some like a good flooding. Some like it leaner. But all examples should be easy starters, cold or hot.

On the move, these side valves like a handful of revs, but they start to get more seriously vibratory at around 50mph. Therefore, you'll probably cruise a little under that speed; maybe a steady 45mph. You'll find that once running, the ignition can usually be fully advanced; you won't have to keep fiddling with it, unlike some other classic motorcycles—except, that is, when on a steep hill or when trickling through traffic, in which case you should retard the ignition to smooth out the power pulses. A little experimentation with the advance and retard lever will improve your control, but avoid riding with the ignition retarded under normal riding conditions; you'll burn out the exhaust valve.

Gearboxes are slow and need a patient foot; tip, count a full second between changes. The clutches are light and reasonably progressive. They shouldn't snatch, so if they do you know that something needs adjusting.

Upon settling in following a rebuild, these old hacks usually become wonderfully reliable, and when things do go wrong, they're generally quickly fixable at the roadside.

You won't need a huge range of tools when travelling. Just make sure that they're all Whitworth, and that you've got some cable nipples, scraps of electrical wire, a spare plug, spare points, HT lead, electrical tape, bulbs, drive chain and primary chain repair kit, plus a handful of nuts and bolts of varying sizes. Better carry a tube of gasket cement too, and some fuel line and fuel line washers/corks, etc.

Girder forks, dampers and handling

Riding these machines takes a little getting used to. If you're not experienced with girder forks, they'll feel very different to teles, being heavier and a little more cumbersome—until, that is, you stop fighting them and sit back in the saddle and give them a little free play.

On rough roads, girders will bounce around a fair bit and will occasionally pogo, but at no time do you ever get the feeling that you're about to be pitched off. It's pretty much the same if riding through potholes; when you see one coming, you instinctively flinch and prepare yourself for a gravel bath. But the heavyweight M-Series sidevalve just steams on and on looking for the next war to fight.

Potholes, therefore, are less of a nuisance than a rippled road, which of course highlights the poor damping of girder models. You can fiddle with the (side) fork damper knob when on the move, but it's doubtful that you'll ever find a happy medium. That said, your riding comfort improves once you ride the M20 within its own terms. You'll get into a rhythm, and then things settle.

Brakes and fuel consumption

The brakes are adequate at the front and a little better at the rear—except for later 600cc examples with an 8-inch front brake which is very good. Our own BSA WM20 has a brake rod conversion on the front. With this arrangement, the brake cable is shortened and stops at a cable lug near the top of the forks. From there, a rod takes over. This is useful because the standard brake actuating arm doesn't have a fine adjustment facility, while the rod conversion offers a wider range of movement. Also, you don't get any stretch in a rod as you might in a cable (not that a cable should stretch more than a few percent when the brake is full on).

Regardless, the rod conversion has improved things a little. The real solution is to have the brake shoes skimmed on a lathe and to fit the softest brake compound you can get.

Fuel consumption at around 40-45mpg is poor (when compared to 500cc OHV singles at 55-60mpg), and there's not a lot you can do about it except ride slowly and eke it out. Old road tests talk of M20s doing up to 70mpg. But to get those kind of figures, you've pretty much got to be pushing it down the street.

Why is the fuel consumption so high? Because it's a side valve. It's as simple as that. The gas flow through a side valve engine is convoluted. At low speeds, the air/fuel mixture can find its way in and out without any major turbulence. But once the piston speed increases, you've got a storm inside that heats up the mixture and the metal and doesn't vent properly. Crudely put perhaps, but essentially that's how it works.

The following information comes from http://www.wdbsa.nl/technical_section.htm

Discontinued in 1963 (1955 for the M20), two engine sizes were listed by the Birmingham Small Arms Company; the 496cc M20 (82mm x 94mm), and the 591cc M21 (85mm x 105mm up to 1938, and 82mm x 112mm thereafter). Both bikes started out with hand change, rigid frames and girder forks. That was pretty much the pre-war state-of-the-side valve-art.

In general, the engines are strong and stress free. They should all start on the first or second kick and settle into a low, steady (and soft) beat. The procedure is straightforward; tickle the carb, set a little retard on the ignition, bring the piston over TDC (with or without the valve lifter) and swing through gently and firmly. And keep in mind that it's really the last few kick start degrees that does the job, so don't ease off halfway down.

Different examples, naturally enough, will have slightly different starting routine. Some want choke. Some don't. Some like a good flooding. Some like it leaner. But all examples should be easy starters, cold or hot.

On the move, these side valves like a handful of revs, but they start to get more seriously vibratory at around 50mph. Therefore, you'll probably cruise a little under that speed; maybe a steady 45mph. You'll find that once running, the ignition can usually be fully advanced; you won't have to keep fiddling with it, unlike some other classic motorcycles—except, that is, when on a steep hill or when trickling through traffic, in which case you should retard the ignition to smooth out the power pulses. A little experimentation with the advance and retard lever will improve your control, but avoid riding with the ignition retarded under normal riding conditions; you'll burn out the exhaust valve.

Gearboxes are slow and need a patient foot; tip, count a full second between changes. The clutches are light and reasonably progressive. They shouldn't snatch, so if they do you know that something needs adjusting.

Upon settling in following a rebuild, these old hacks usually become wonderfully reliable, and when things do go wrong, they're generally quickly fixable at the roadside.

You won't need a huge range of tools when travelling. Just make sure that they're all Whitworth, and that you've got some cable nipples, scraps of electrical wire, a spare plug, spare points, HT lead, electrical tape, bulbs, drive chain and primary chain repair kit, plus a handful of nuts and bolts of varying sizes. Better carry a tube of gasket cement too, and some fuel line and fuel line washers/corks, etc.

Girder forks, dampers and handling

Riding these machines takes a little getting used to. If you're not experienced with girder forks, they'll feel very different to teles, being heavier and a little more cumbersome—until, that is, you stop fighting them and sit back in the saddle and give them a little free play.

On rough roads, girders will bounce around a fair bit and will occasionally pogo, but at no time do you ever get the feeling that you're about to be pitched off. It's pretty much the same if riding through potholes; when you see one coming, you instinctively flinch and prepare yourself for a gravel bath. But the heavyweight M-Series sidevalve just steams on and on looking for the next war to fight.

Potholes, therefore, are less of a nuisance than a rippled road, which of course highlights the poor damping of girder models. You can fiddle with the (side) fork damper knob when on the move, but it's doubtful that you'll ever find a happy medium. That said, your riding comfort improves once you ride the M20 within its own terms. You'll get into a rhythm, and then things settle.

Brakes and fuel consumption

The brakes are adequate at the front and a little better at the rear—except for later 600cc examples with an 8-inch front brake which is very good. Our own BSA WM20 has a brake rod conversion on the front. With this arrangement, the brake cable is shortened and stops at a cable lug near the top of the forks. From there, a rod takes over. This is useful because the standard brake actuating arm doesn't have a fine adjustment facility, while the rod conversion offers a wider range of movement. Also, you don't get any stretch in a rod as you might in a cable (not that a cable should stretch more than a few percent when the brake is full on).

Regardless, the rod conversion has improved things a little. The real solution is to have the brake shoes skimmed on a lathe and to fit the softest brake compound you can get.

Fuel consumption at around 40-45mpg is poor (when compared to 500cc OHV singles at 55-60mpg), and there's not a lot you can do about it except ride slowly and eke it out. Old road tests talk of M20s doing up to 70mpg. But to get those kind of figures, you've pretty much got to be pushing it down the street.

Why is the fuel consumption so high? Because it's a side valve. It's as simple as that. The gas flow through a side valve engine is convoluted. At low speeds, the air/fuel mixture can find its way in and out without any major turbulence. But once the piston speed increases, you've got a storm inside that heats up the mixture and the metal and doesn't vent properly. Crudely put perhaps, but essentially that's how it works.

The following information comes from http://www.wdbsa.nl/technical_section.htm