|

This German World War II helmet was simply called the Stahlhelm. "Stahlhelm" is a German word that means "steel helmet". It was derived from a helmet design first introduced into regular service during World War I in early 1916. Changes to the helmet design were made after World War I, and by World War II three main versions of this helmet were worn.

The first version was introduced before World War II, in 1935. Often referred to as the M1935, it was made by pressing sheets of molybdenum steel in several stages. It had ventilator holes that were set in hollow fittings mounted to the helmet's shell. The edges of the shell were rolled over, creating a smooth edge along the helmet. It also had a new leather suspension, or liner, that was incorporated to improve the helmet's safety, adjustability, and comfort for each wearer. These improvements made the new M1935 helmet lighter, more compact, and more comfortable to wear than the previous designs. The German armed forces officially accepted the new helmet on June 25, 1935 and it was intended to replace all other helmets in service. The second version was introduced in 1940. It was a modification of the M1935 to simplify its construction. The manufacturing process of the helmet incorporated more automated stamping methods. The principal change was to stamp the ventilator hole mounts directly onto the shell, rather than utilizing separate fittings. In other respects, the M1940 helmet was identical to the M1935. The Germans still referred to the M1940 as the M1935, while the M1940 designation was given to this version by collectors after the war. The third version was introduced in 1942. This design was a result of continuing wartime demands. The rolled edge on the helmet shell was eliminated, creating an unfinished edge along the rim. The elimination of the rolled edge expedited the manufacturing process and reduced the amount of metal used in each helmet. Manufacturing flaws were also observed in M1942 helmets made late in the war. The three helmet types were painted in several different colors or camouflage patterns as the war progressed. The colors varied from traditional grey to a dark yellow shade, and even to white for winter camouflage. Other markings sometimes included decals or insignia for the various branches of the German armed forces. These were often applied to the sides of the Stahlhelm during the war. However, on August 28th 1943, the helmet factories were ordered to stop applying these decals. By halting the application of all decals, these factories could save time and money, thus simplifying production at a time when the war was already turning against Germany. At the end of the war, many of these helmets were brought back to the United States by victorious American soldiers. Later, such helmets were bought and sold by collectors, or added to the collection of many museums. Our helmet appears to be a Model 1942 Stahlhelm. It has one decal of the type that was placed on helmets used by the German Army.

0 Comments

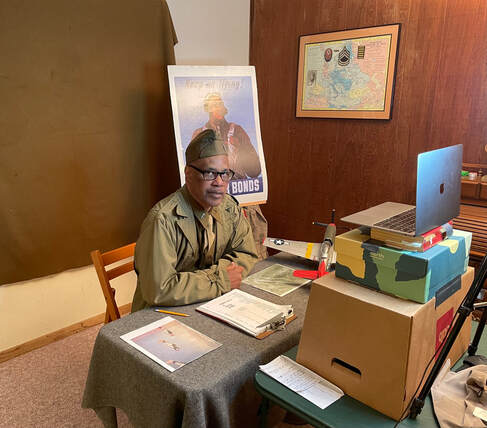

From COVID to zoom and back- WWII Reenactor Joel Brown in a three part series presents live the story of the Black Air Force of WWII. Join us for part one on April 9, 2022.

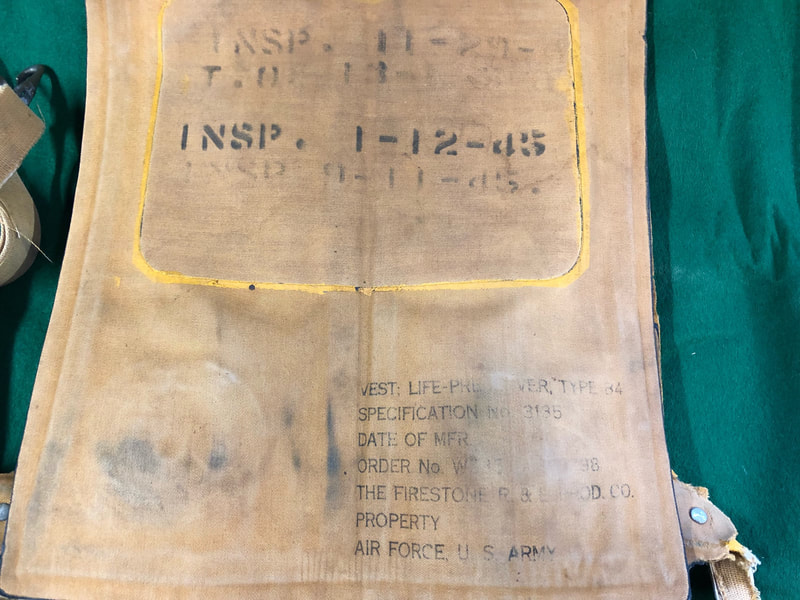

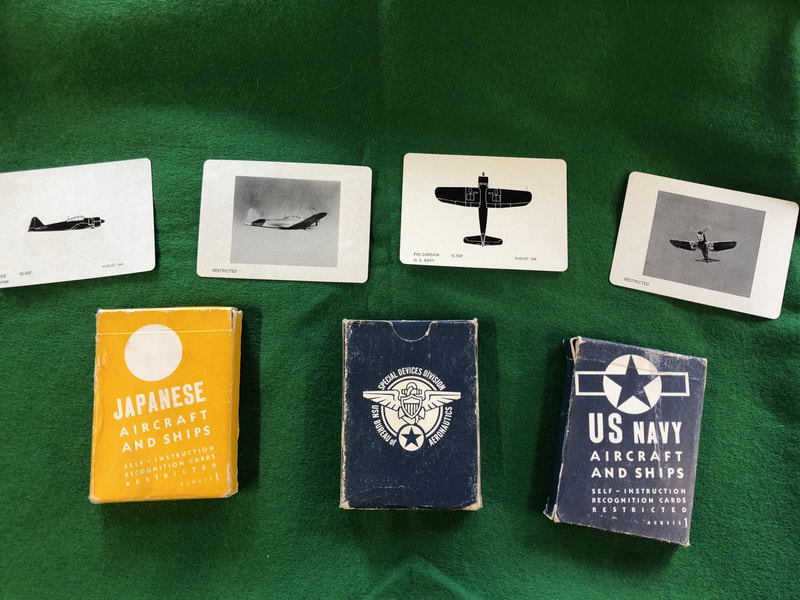

This event is presented by CAF MN Wing & Joel Brown. This event is free to the public, but we ask that you register so we know how many people will be attending. This month’s featured artifact from the MN CAF archives is the U.S. Army B-4 life preserver. Our example was manufactured by the Firestone Rubber and Latex Products Company. The manufacture date is no longer readable, but it has a clear inspection date of 1-12-45, making this a nice wartime example. The USAAF Pneumatic Life Vest was a yellow rubber life vest that inflated using liquid CO2 cartridges in the vest that were activated by pulling on two cords at the bottom of the vest. When released, the liquid turned to gas and quickly inflated the pockets of the vest. As a back-up, rubber inflation tubes were incorporated into the front of the vest near the neck hole and could be blown into and manually inflate the vest. Fully inflated, the wearer of the vest resembled a buxom woman. This resulted in the WWII men who wore them to begin referring to them as ‘Mae Wests’, aptly named after the well-endowed film star of the time. What many do not know is that the inflatable life preserver was invented by a Minnesota man by the name of Peter Markus. Markus was a merchant living in Minnesota and was an avid boater and fisherman. He was attuned to the fact that fishermen were falling out of their boats and drowning because they were unwilling to wear the bulky life preservers of the time, which were filled with cork and hindered arm movement while fishing. He started experimenting and invented a new style device based on a man’s vest. It slipped over the head and had waist straps sewn into the front that could be secured behind the back. Markus received a patent for his invention in 1928, with patented changes in 1930 and 1931. A Navy captain happened to catch Markus demonstrating the device during a sportsman’s show and quickly realized its military value. Markus was invited to Washington to demonstrate it for the military brass. Shortly after, the Navy began purchasing them. The value of the vest became apparent soon after when an aviator in Hawaii and his passenger put their plane down in the water off Honolulu. The pilot was wearing the vest, but the passenger was not. Only the pilot survived. It was a powerful message and soon after, the vests became regulation equipment for all Navy fliers, as well as being incorporated into the other branches of the service shortly thereafter. The investment paid off handsomely when in 1935, the rigid airship, U.S.S. Macon went down in the Pacific and 98 of the 100 vest-wearing crew survived. During WWII, Peter Markus’ pneumatic vest was worn by fighter pilots, bomber and transport crews and even the paratroopers crossing the English Channel enroute to Normandy on D-Day. Whether it was over the Atlantic, Pacific or the Mediterranean, his device no doubt saved the lives of thousands of soldiers during WWII. Photo credits Commemorative Air Force Minnesota Wing, toflyandfight.com and the National Archives. This month’s featured artifact is this U.S. Government issued aircraft recognition model of the P-2V Neptune. The P-2 first flew in May of 1945 and was put in production too late for service in WWII but later served as a maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare aircraft during the Cold War.

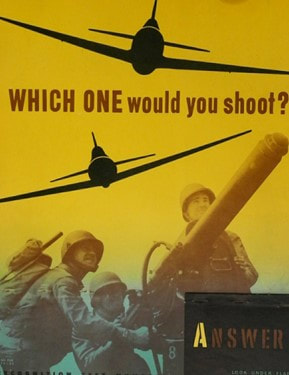

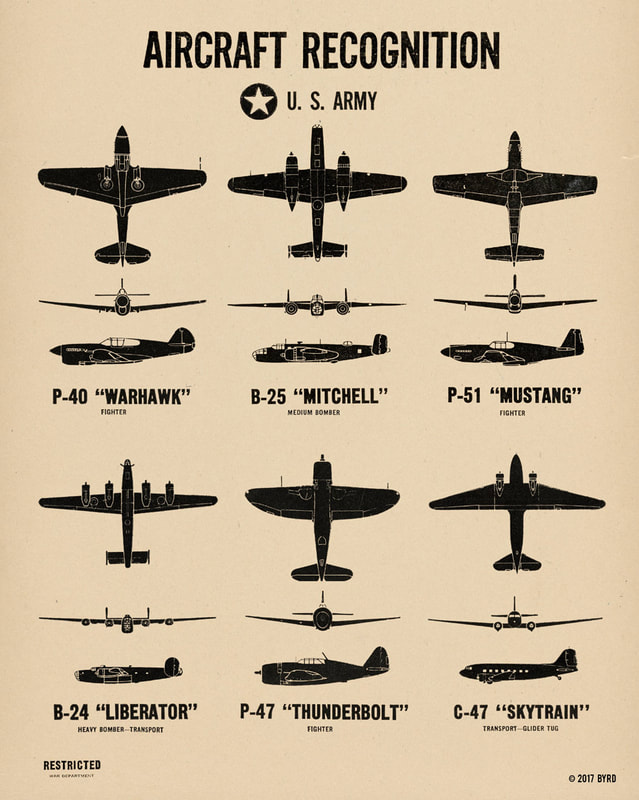

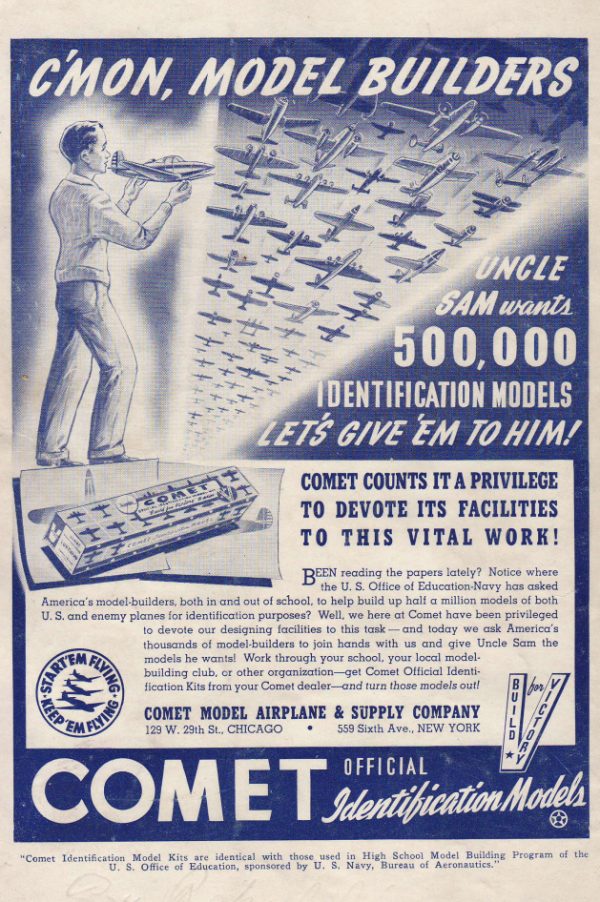

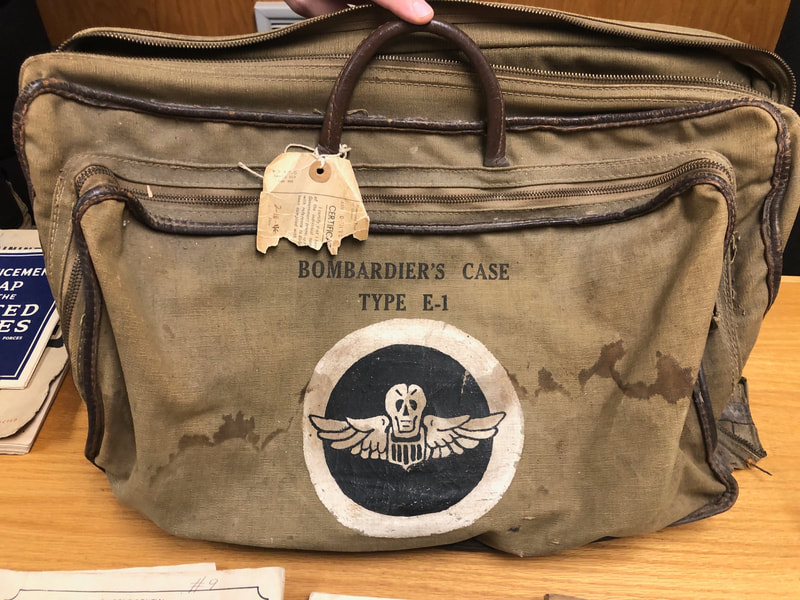

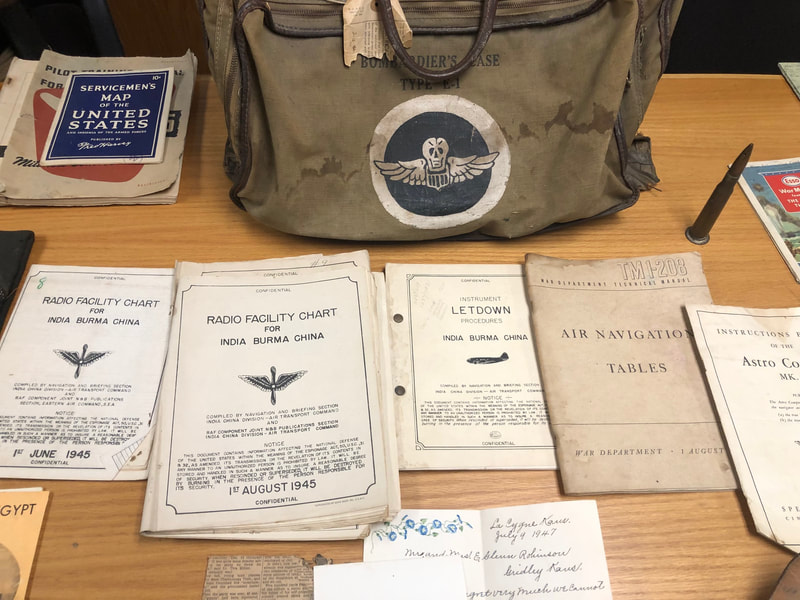

As WWII unfolded, the importance of aircraft recognition became increasingly apparent. Aircraft recognition models, also known as ‘spotter’ or ‘i.d.’ models were produced by the thousands and used for training purposes for both military personnel and civilians alike. These models were painted flat black and lacked any real surface detail or markings in order to simulate a silhouette. Air crewmen, anti-aircraft personnel as well as civil defense workers were required to quickly identify an aircraft based solely on its general outline and major surface features such as its fuselage and wing shape, tail surfaces or number of engines from all possible angles. The importance of getting it right could mean the difference between targeting a friendly aircraft or allowing an enemy aircraft to fly by unscathed. It was also crucial for civilian ground spotters to correctly identify aircraft passing over in order to relay important information such as: number of aircraft, direction of flight and altitude to military authorities so that intercept aircraft could be scrambled. Aircraft spotting and identification was vital for civilian defense. Accurate identification was essential in order to sound off air-raid warnings and give civilians and wartime workers the crucial extra minutes to take shelter, whereas a false alarm would cause an unnecessary disruption to production output. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the U.S. Bureau of Aeronautics put out a request for schoolchildren to produce over 500,000 scale aircraft models out of balsa wood to help civilians and soldiers differentiate friend from foe. As the uncertain nature of the war progressed, especially after German submarine sightings off the East Coast and Japanese shelling on the West Coast, aircraft recognition became an important, useful and even fun pastime for civilians and children. Millions of posters, publications, advertisements and even children’s games were produced during the war as an educational tool for identifying aircraft. Our P-2V is made from mold injected resin and has a 17” wingspan and is 13” in length. After the war, these models became surplus and were sold by the thousands in Army/Navy surplus stores throughout the country and are considered collectible items today. This month’s featured artifact is an original WWII E-1 Bombardier’s bag that belonged to 1st Lt. Scott A. Mouse of Emporia, Kansas. Lt. Mouse was a bombardier-navigator and served with the 490th Bomb Squadron of the 10th & 14th Air Forces, infamously known as the ‘Burma Bridge Busters’.

The 490th Bomb Squadron flew innumerable missions in the (C.B.I.) China, Burma and India Theatre– often referred to as the “forgotten theater” of WW2. Activated in Karachi, British India as a B-25 Mitchell bomber squadron, the Burma Bridge Busters flew 615 missions between February 1943 and August 1945. During this period, the squadron dropped over 8,257,000 pounds of bombs and destroyed 192 bridges. Operating under the 10th Air Force, the squadron also carried out tactical interdiction missions against Japanese communications lines and supported the British ground forces in Burma between 1943 and 1944. In January 1944, Squadron Leader Major Robert A. Erdin accidentally discovered a bridge-destroying skip bombing technique. After perfecting this skip-bombing technique and using it regularly during missions, the squadron was nicknamed ‘Burma Bridge Busters’ by the general in command of the Tenth Air Force. A year later, the squadron assumed another role – dropping propaganda flyers over Burma for the U.S Office of War Information. In April 1945, the squadron was reassigned to the 14th Air Force in China. Until the end of the war, they continued to disrupt enemy communication lines and provided support to Chinese ground forces. The primary objective of the squadron was to keep the Chinese in the war simply because this would tie down the nearly one million Japanese troops preventing them from operating elsewhere. During its three years of service, the 490th squadron received more than 1,000 individual citations, destroyed 192 bridges in China, Burma and India, and won two Distinguished Unit Citations. This navigator’s bag was graciously donated to us by Lt. Mouses’ family this past summer during a stopover in Iola, Kansas with our own B-25J, Miss Mitchell. The bag contains a treasure trove of original manuals, maps, a first aid kit and even a pistol holster belonging to Mouse. These items are a wonderful tribute To Lt. Mouse and to all the brave B-25 Mitchell crews that served during WWII. War bonds were debt securities by the U. S. Government. A debt security represents a promise to payback the face amount of the debt plus interest once it matures. In other words, when a person purchased a war bond, it represented a loan of a fixed amount of money to the government, to be repaid with interest.

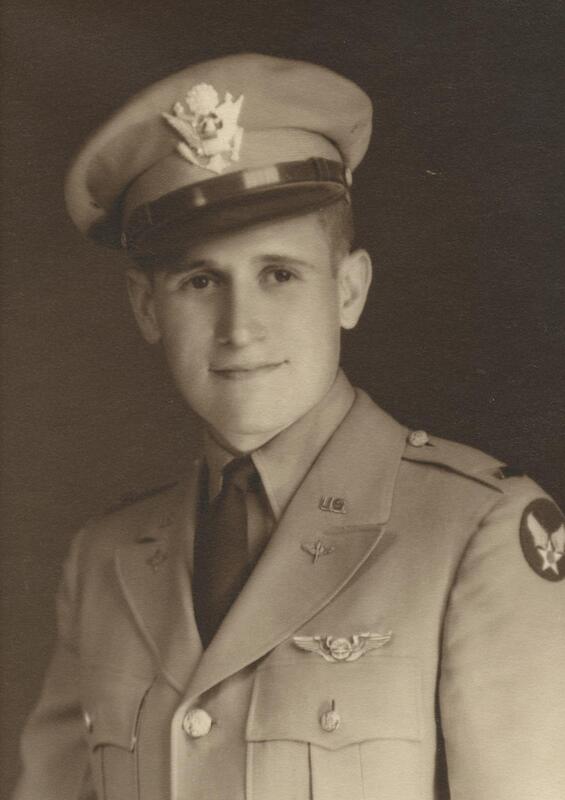

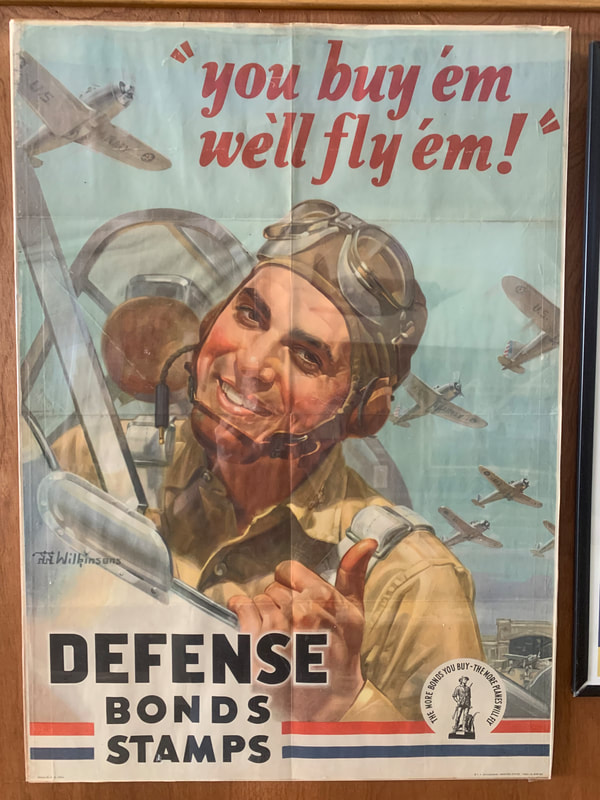

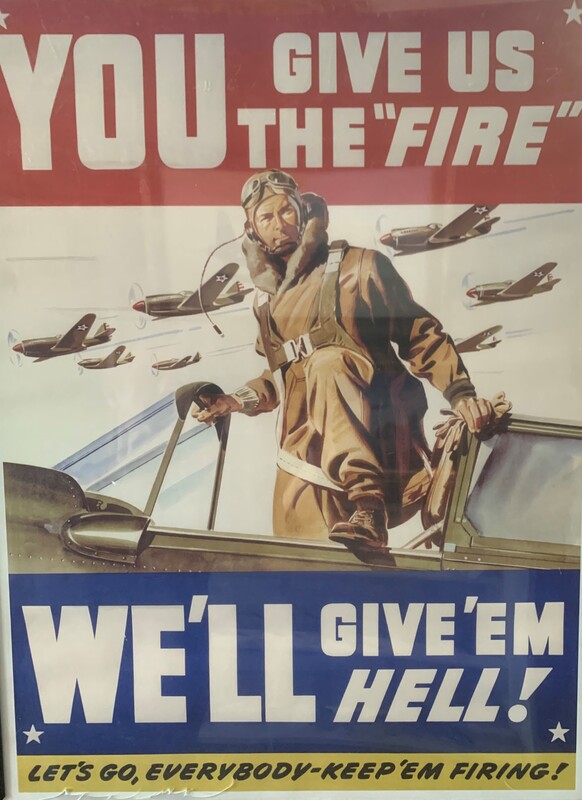

Instead of paying the total cost for a war bond at one time, war savings stamps could also be used. The stamps were available in denominations of 10 cents, 25 cents, 50 cents, 1 dollar, and 5 dollars. When enough of them were collected, they could be exchanged for a 25 dollar bond. During WWII, war bonds were issued by the government to finance military operations and other wartime expenditures. At a time when full employment collided with rationing, war bonds were also seen as a way to remove money from circulation in order to reduce inflation. Representing both a moral and financial stake in the war bonds, despite the war’s hardships. By means of advertising, an emotional appeal went out to citizens to buy war bonds and stamps. Both the government and the private companies created advertisements like the posters seen here.

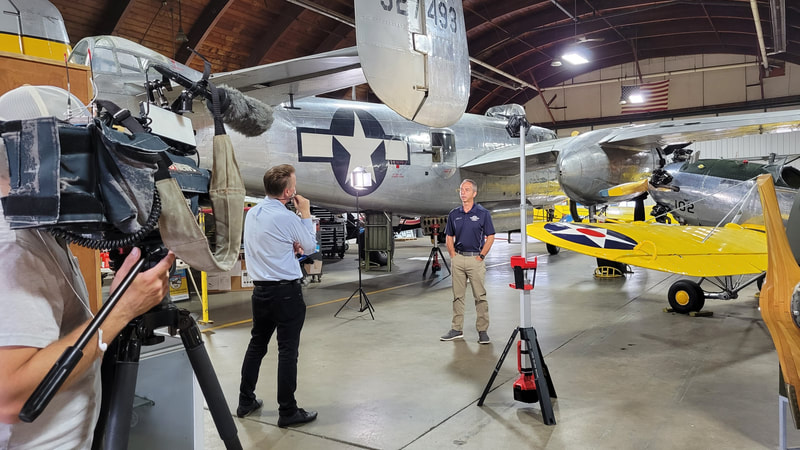

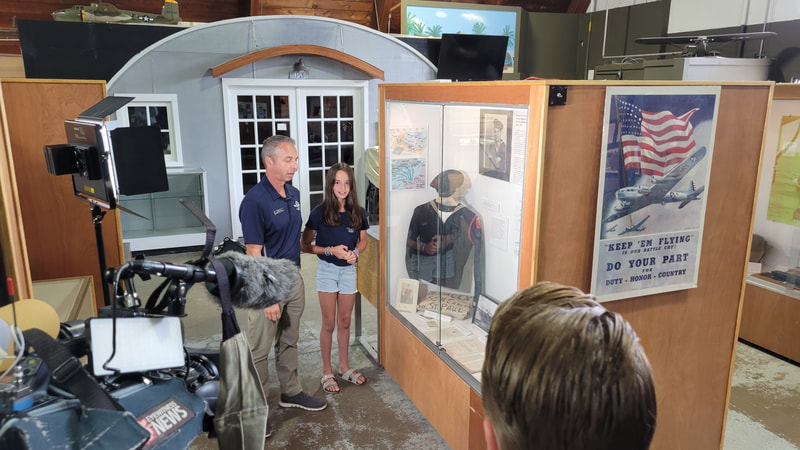

This month the museum had the pleasure of being on Channel 5 Eyewitness News series called "So Minnesota". It showacases the people, places and things unique to our state. Here is a link to the story, we hope you like it.

Special visitor Ken Axelson is a 97 year old WWII veteran who visited our museum with his family. During the war he served as combat medic, landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day. He later went through two weeks of intensive paratrooper training when the 101st Airborne needed medics, was in the Battle of the Bulge (Bastogne), and spent three months as a prisoner of war in Germany.

While he was visiting us he shared some of his story with other museum visitors, and with CAF members. We were honored to have him visit us. You can learn more about Ken in a 2014 Pioneer Press article found here: https://www.twincities.com/.../70-years-on-d-day-veteran.../

The Commemorative Air Force Minnesota Wing is more than just a museum. We are all volunteers with a mission and a purpose. While each of our reasoning is different for volunteering, we all agree - THIS is more than just a museum. Whether you volunteer, donate, attend an event, or take a history flight ride, your contributions help us continue to educate, restore, and honor.

Thank you to Hemlock Films for this amazing commercial: Director - Kara White, Cinematographer - Adam White, and Sound Recordist- Kevin Hines. You can view more of their work by their website. Special visitors to the museum this month were two P-51 Mustangs. The sleek P-51 Mustang is perhaps the best all-around fighter of World War II. In 1939, British officials approached North American Aviation in desperate need of additional aircraft for the war in Europe. Just 117 days after the order was placed, the first P-51 was rolled out of the factory.

Equipped with an American-built copy of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, the P-51 quickly became one of the best-known and most feared fighters in the world—able to escort heavy bombers deep into enemy territory. A total of 15,567 Mustangs of all types were built for the Army and foreign nations. In combat, they destroyed nearly 6,000 enemy aircraft, making the Mustang the deadliest Allied fighter of World War II. The CAF Red Tail Squadron’s P-51C Mustang, named Tuskegee Airmen, is an authentic and fully restored operational fighter from the WWII era. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC), a precursor of the U.S. Air Force. Trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, they flew more than 15,000 individual sorties in Europe and North Africa during World War II. Their impressive performance earned them more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, and helped encourage the eventual integration of the U.S. armed forces. This awe-inspiring aircraft sparks conversations to educate young and old alike about the often-overlooked history of the Tuskegee Airmen that flew this same model as their signature aircraft in WWII. The Mission of the P-51 Quick Silver is to honor and pay tribute to the veterans that have sacrificed their lives for the freedom and security of others. Quick Silver is a celebration of our nation’s armed forces. Every aspect of the paint represents those who have served, and those who gave the ultimate sacrifice. The black cape covering the front of the aircraft represents the veil of protection that our armed forces give us. That veil is one of the reasons why we have what we have today, freedom. As the cape extends to the back of the canopy, it spreads out and divides into feathers, symbolizing the eagle that has flown with every aviator since the birth of aviation in 1903. The black paint has tiny sparkling stars in it, each sparkle represents an American Veteran that served our great country; the unsung stars in our lives. These veterans are the glimmering star in a mother’s eye, a wife or husband’s heart, a son or daughter’s hope for the future. The silver ring behind the spinner represents the shinning halo of the guardian angel who guides service personnel, having given the ultimate sacrifice, to their final resting place. The black and white stripes on the wings are there, as they were on all allied aircraft on D-day. The stars and bars, proudly displayed, represent the armed forces symbol that all United States fighter planes carry. It carries the post war version because “Quick Silver” was never a part of a unit till after World War II. All of the bare metal of this P-51 Mustang is polished. Look closely into the metal, you can see for whom our veterans fought. |

AuthorWelcome to the CAF MN Wing Blog. You will find information on projects we are working on, upcoming events, and more. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed